Feature Stories & Analysis

For the past two years, I worked as a journalist at Law360 where I wrote multiple stories each day related to the latest court filings in immigration, government contracts and international trade. I've also worked on feature stories at Law360 that looked at opportunities based on gender among attorneys vying for Supreme Court oral arguments, and have written about international topics for our Access to Justice wire.

What’s In A Judgeship? More Than Meets The Eye

By Amanda James | March 20, 2019

For many judges in federal court, the size of their dockets is more than double what court officials have deemed a manageable workload.

Last week, the Judicial Conference of the United States, which makes recommendations to Congress every two years on the need for additional judgeships, called for adding 73 permanent positions across 27 districts nationwide. All but three of those districts had average weighted caseloads above the recommended amount of 430.

More in this series:

When caseloads creep above that level, courts face difficulty maintaining their dockets, according to U.S. District Judge Roslynn Mauskopf, who helped come up with the recommendations as chair of the Judicial Conference’s Subcommittee on Judicial Statistics. But in districts like Louisiana’s Eastern, Indiana’s Southern, Delaware and New Jersey, weighted caseloads are more than 900 per judgeship. The 430 benchmark was last updated in 2005 and affirmed again in 2015.

Cases are weighted for complexity. So, for example, a case involving a defaulted student loan is counted as 0.16, while an antitrust case is counted as 3.72 cases. The Judicial Conference last changed the case weights in 2016, based on survey responses from judges and national data that shows how time-consuming different types of cases are.

But it takes more than simply measuring judges’ caseloads to see how districts are overburdened — wait times for trial, population growth and even geography come into play. So begins a complicated process to determine which of 94 districts should get the scarce and coveted resource of additional judgeships.

If the only factor in deciding how many judges are needed per district meant making sure each judgeship’s weighted caseload didn’t surpass 430, then there would need to be more than 120 additional judgeships, almost twice the amount recommended last week. But there are other factors to consider.

“If we could rely on putting these numbers in a computer and it spit out the number of judges a district needed, that would be nice, but Congress isn’t going to leave that kind of decision up to a computer,” said Russell Wheeler, a fellow at the Brookings Institution and former deputy director of the Federal Judicial Center.

Congress passed the last major judgeship bill in 1990. Since then, judicial ranks have grown about 4 percent while filings have soared by 38 percent. The number of filings climbed from about 265,000 in 1992 to 391,000 in 2018, according to data from the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

Despite the new recommendations, Congress isn’t likely to act. Partisan gridlock has kept Congress from adding new judgeships since 2003.

The recommendations, if adopted, would help bring the bench in line with modern population and caseload statistics, alleviating odd disparities that have arisen in how resources are allocated across districts.

For example, a judge in Indianapolis has more than three times the weighted caseload — 991 cases — than that of a judge in Pittsburgh, where the caseload is 304 per judge. Yet, the Western District of Pennsylvania has twice the number of judgeships, 10, as the Southern District of Indiana, with five, according to federal court data.

Vacancies introduce another wrinkle. While the caseload in Southern Indiana is high, all the positions are filled. Judges in Pittsburgh are inevitably working on more cases than the data shows, since four of their judgeship positions are vacant.

There are currently 129 federal district court vacancies nationwide. To address the shortage, courts use various stopgap measures such as relying on senior judges, who can choose whether to maintain a full docket, shrink their caseload or fully retire. They also rely on magistrate judges, whose jurisdictions are limited, and visiting judges, who serve in other districts.

Take the Central District of California, for example. Congress has approved 28 judgeships, but eight spots are vacant, so there are only 20 active judges, including one temporary judge. The district uses a mix of magistrate judges and senior judges to pick up the slack.

In past years, the Judicial Conference has recommended temporary judges as stopgaps, roles that have expiration dates; however, this year’s recommendations didn’t include any temporary positions.

“The judiciary has taken a comprehensive approach reflecting needs of districts across the country and these are long-standing problems that require a permanent solution, not a temporary one,” Judge Mauskopf said.

California, which has about 10 percent of the nation’s caseload, saw a 13.5 percent increase in cases filed from 2003 to 2018.

“The effects of this kind of caseload increase is profound. Increasing caseloads leads to significant delays in the consideration of cases, especially civil cases, which may take years to get to trial,” Judge Mauskopf said.

In 13 judicial districts, the median number of months it takes to bring a civil case to trial is more than three years, meaning getting your case before a jury could take longer than getting a law degree. That includes New York’s Western District, where civil cases can take more than five years.

Not everybody agrees on the need for new judgeships, however. Judith Resnik, the Arthur Liman professor of law at Yale Law School, noted that some districts have under 250 cases per judge, not including magistrate judges.

Since judges can sit by designation, judges in districts with low-weighted caseloads could be designated to help higher-volume districts, she said.

“Given technology, much of that work can be done from the judge’s home base,” Resnik said.

Amanda James is a data reporter for Law360. She last wrote about how the lack of identification impedes access to justice around the world. Follow her on Twitter. Graphics by Chris Yates. Editing by Jocelyn Allison, Katherine Rautenberg and John Campbell.

By Amanda James | March 20, 2019

For many judges in federal court, the size of their dockets is more than double what court officials have deemed a manageable workload.

Last week, the Judicial Conference of the United States, which makes recommendations to Congress every two years on the need for additional judgeships, called for adding 73 permanent positions across 27 districts nationwide. All but three of those districts had average weighted caseloads above the recommended amount of 430.

More in this series:

- As Judicial Ranks Stagnate, 'Desperation' Hits The Bench

- These Are The Nation’s 27 Most Overworked District Courts

- ‘In A Timely Manner’: Three Decades Of Judgeship Bills

- From Showdowns To Hotlines, Frazzled Judges Get Creative

- Swamped: How Magistrate Judges Salvaged Louisiana's Judicial Crisis

When caseloads creep above that level, courts face difficulty maintaining their dockets, according to U.S. District Judge Roslynn Mauskopf, who helped come up with the recommendations as chair of the Judicial Conference’s Subcommittee on Judicial Statistics. But in districts like Louisiana’s Eastern, Indiana’s Southern, Delaware and New Jersey, weighted caseloads are more than 900 per judgeship. The 430 benchmark was last updated in 2005 and affirmed again in 2015.

Cases are weighted for complexity. So, for example, a case involving a defaulted student loan is counted as 0.16, while an antitrust case is counted as 3.72 cases. The Judicial Conference last changed the case weights in 2016, based on survey responses from judges and national data that shows how time-consuming different types of cases are.

But it takes more than simply measuring judges’ caseloads to see how districts are overburdened — wait times for trial, population growth and even geography come into play. So begins a complicated process to determine which of 94 districts should get the scarce and coveted resource of additional judgeships.

If the only factor in deciding how many judges are needed per district meant making sure each judgeship’s weighted caseload didn’t surpass 430, then there would need to be more than 120 additional judgeships, almost twice the amount recommended last week. But there are other factors to consider.

“If we could rely on putting these numbers in a computer and it spit out the number of judges a district needed, that would be nice, but Congress isn’t going to leave that kind of decision up to a computer,” said Russell Wheeler, a fellow at the Brookings Institution and former deputy director of the Federal Judicial Center.

Congress passed the last major judgeship bill in 1990. Since then, judicial ranks have grown about 4 percent while filings have soared by 38 percent. The number of filings climbed from about 265,000 in 1992 to 391,000 in 2018, according to data from the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

Despite the new recommendations, Congress isn’t likely to act. Partisan gridlock has kept Congress from adding new judgeships since 2003.

The recommendations, if adopted, would help bring the bench in line with modern population and caseload statistics, alleviating odd disparities that have arisen in how resources are allocated across districts.

For example, a judge in Indianapolis has more than three times the weighted caseload — 991 cases — than that of a judge in Pittsburgh, where the caseload is 304 per judge. Yet, the Western District of Pennsylvania has twice the number of judgeships, 10, as the Southern District of Indiana, with five, according to federal court data.

Vacancies introduce another wrinkle. While the caseload in Southern Indiana is high, all the positions are filled. Judges in Pittsburgh are inevitably working on more cases than the data shows, since four of their judgeship positions are vacant.

There are currently 129 federal district court vacancies nationwide. To address the shortage, courts use various stopgap measures such as relying on senior judges, who can choose whether to maintain a full docket, shrink their caseload or fully retire. They also rely on magistrate judges, whose jurisdictions are limited, and visiting judges, who serve in other districts.

Take the Central District of California, for example. Congress has approved 28 judgeships, but eight spots are vacant, so there are only 20 active judges, including one temporary judge. The district uses a mix of magistrate judges and senior judges to pick up the slack.

In past years, the Judicial Conference has recommended temporary judges as stopgaps, roles that have expiration dates; however, this year’s recommendations didn’t include any temporary positions.

“The judiciary has taken a comprehensive approach reflecting needs of districts across the country and these are long-standing problems that require a permanent solution, not a temporary one,” Judge Mauskopf said.

California, which has about 10 percent of the nation’s caseload, saw a 13.5 percent increase in cases filed from 2003 to 2018.

“The effects of this kind of caseload increase is profound. Increasing caseloads leads to significant delays in the consideration of cases, especially civil cases, which may take years to get to trial,” Judge Mauskopf said.

In 13 judicial districts, the median number of months it takes to bring a civil case to trial is more than three years, meaning getting your case before a jury could take longer than getting a law degree. That includes New York’s Western District, where civil cases can take more than five years.

Not everybody agrees on the need for new judgeships, however. Judith Resnik, the Arthur Liman professor of law at Yale Law School, noted that some districts have under 250 cases per judge, not including magistrate judges.

Since judges can sit by designation, judges in districts with low-weighted caseloads could be designated to help higher-volume districts, she said.

“Given technology, much of that work can be done from the judge’s home base,” Resnik said.

Amanda James is a data reporter for Law360. She last wrote about how the lack of identification impedes access to justice around the world. Follow her on Twitter. Graphics by Chris Yates. Editing by Jocelyn Allison, Katherine Rautenberg and John Campbell.

Access By The Numbers

Who Are You Without An ID?

By Amanda James | March 3, 2019

When Mahmoud Hussein's wallet was stolen by a pickpocket, he knew he needed to get a new ID card immediately.

In Kenya, a person needs an ID card to vote, enroll in school, get a job, obtain a driver's license, file a police report and, in some cases, to enter a law office or courtroom.

But faced with hurdles including multiple vetting processes by committees of elders and security personnel who demanded to see more paperwork than he could provide, he didn't get a new one for 29 years.

Meanwhile, he had to rely on his wife's income and struggled to make ends meet, according to a spokesperson for Namati, a nonprofit organization that helped Hussein obtain an ID.

Hussein was among the 1 billion people across the globe who face challenges in proving who they are because they lack official proof of their identity.

As a result, they struggle to access basic services including health care and education, as well as obtaining a cellphone, using a bank card or finding a job, according to the World Bank, which gathered the data as part of its Identification for Development initiative, or ID4D.

Citizens may also not be able to access justice through their country's civil and criminal justice systems when they lack an ID, and while IDs may be taken for granted in developed countries, they are connected to nearly every facet of life.

"Without an ID, in many countries, you're invisible," said Laura Goodwin, director of Namati's citizenship program in Kenya, which trains locals in developing countries to be legal advocates. "You don't exist in the eyes of the state."

Goodwin is based in Kenya, where around 9 percent of the population over age 15 lacks a national ID, or about 2.7 million people. In Nairobi, Namati trains local Kenyans to become paralegals and help other Kenyans to get IDs, including Mahmoud.

"The vulnerability of not having an ID opens people up to exploitation and corruption," Goodwin said.

Within a city or between cities there are often police checkpoints where a traveler needs to have an ID. To fill out a police report, or enter a government building, you may need an ID, including to go to court. Sometimes, without an ID, people are asked to pay a bribe to the police, Goodwin said.

Even with the number of Kenyans who lack IDs, the country still fares better than many others.

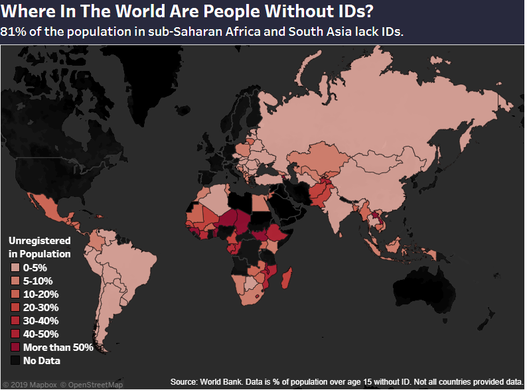

Of the 1 billion people without IDs, 81 percent live in sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia. South Sudan, Chad and Armenia are among the countries with the highest share of unregistered population, according to World Bank data on people over age 15. Those countries also have a high rate of the population without a birth registration. For example, UNICEF data shows that only 35 percent of the population in South Sudan has a birth registration, and only 12 percent in Chad.

"Without a secure and trusted way to prove their identity, people struggle to open a bank account, enroll in school, access health and social services, or obtain a mobile phone," said Vyjayanti Desai, program manager for the ID4D Initiative.

The obstacles people face in getting an ID may be the result of discrimination, illiteracy, large distances to ID registration points, cost, time, and not knowing their right to an ID.

Many countries with large populations of residents without IDs also have high measures of corruption, discrimination or improper government influence in their civil justice systems, according to data from the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index. The index ranks countries based on the quality of their justice systems, and is separate from World Bank data but shows some overlap. In many of the worst-ranked countries for civil justice, nearly 20 percent of the population over the age of 15 does not have an ID.

That includes Guatemala, Cameroon, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

"Access to justice is being able to obtain a just resolution and enforce your rights," said Sarah Long, director of the Rule of Law Index. "Having legal ID helps people assert their rights when they run into issues accessing basic public services and benefits they're entitled to."

Once a person has one legal problem, that can snowball into more legal issues, according to Long, who calls that "problem clustering."

"Problems with legal identity or citizenship can bring about other legal problems, such as trouble accessing health care, education or other public services," Long said.

The ID problem appears to be worse among women.

According to the 2017 ID4D-Findex survey, in low-income countries more than 45 percent of women lack an ID, compared to 30 percent of men, a situation that disproportionately limits how women can participate in economic and political life in their country.

For example, in Afghanistan, half of the women surveyed did not have an ID compared with 6 percent of the men surveyed. In Chad, nearly 80 percent of women lacked an ID, compared with 45 percent of men.

A variety of social barriers can play into those gaps.

Child marriage is more common among women in countries with relatively few women with IDs, and in those countries women are less likely to participate in the labor force, according to the World Bank.

In Afghanistan, Benin, and Pakistan — all countries with ID gender gaps of more than 15 percentage points — a married woman can't even apply for a national ID in the same way as a married man, according to the World Bank in its Women, Business and Law report.

There is also a connection between a country's income and IDs.

According to ID4D data, 63 percent of people without IDs live in lower-middle income economies, and 28 percent live in low-income economies.

Those numbers reinforce the fact "that lack of identification is a critical concern for the global poor," Desai wrote on a World Bank blog.

Momentum could be building to tackle the ID problem, though the path forward remains hazy.

The United Nations has made the issue one of its "sustainable development goals" and set a target that by 2030 there will be legal identity for all, including birth registration. However, it hasn't specified how it plans to reach that target.

But some progress is being made. A U.N. report from 2018 shows that more children in sub-Saharan Africa under age 5 now have birth registration than in 2016. Some countries, such as Malawi, have made huge strides. Between 2017, when the World Bank collected data, and 2018, Malawi's population went from 87 percent of people without ID to about 90 percent with an ID.

Multiplying such gains will take a holistic approach, according to experts.

Goodwin, who works with populations in Bangladesh and Kenya who face exclusion and discrimination, points out that even when more people in a country gain IDs, it's important to address the underlying barriers.

She said it's important to ask, "Who is getting left out?"

--Editing by Brian Baresch.

Data from the ID4D Findex Survey was collected as part of the 2017 Gallup World Poll and includes data from 99 economies. Survey respondents were over age 15 and asked whether they personally had a specific national ID. Birth certificates, voter IDs, etc. were not included. The percentages of a population without an ID are estimates, as there is no standard, agreed-upon approach to measure the number of people without legal identity.

Who Are You Without An ID?

By Amanda James | March 3, 2019

When Mahmoud Hussein's wallet was stolen by a pickpocket, he knew he needed to get a new ID card immediately.

In Kenya, a person needs an ID card to vote, enroll in school, get a job, obtain a driver's license, file a police report and, in some cases, to enter a law office or courtroom.

But faced with hurdles including multiple vetting processes by committees of elders and security personnel who demanded to see more paperwork than he could provide, he didn't get a new one for 29 years.

Meanwhile, he had to rely on his wife's income and struggled to make ends meet, according to a spokesperson for Namati, a nonprofit organization that helped Hussein obtain an ID.

Hussein was among the 1 billion people across the globe who face challenges in proving who they are because they lack official proof of their identity.

As a result, they struggle to access basic services including health care and education, as well as obtaining a cellphone, using a bank card or finding a job, according to the World Bank, which gathered the data as part of its Identification for Development initiative, or ID4D.

Citizens may also not be able to access justice through their country's civil and criminal justice systems when they lack an ID, and while IDs may be taken for granted in developed countries, they are connected to nearly every facet of life.

"Without an ID, in many countries, you're invisible," said Laura Goodwin, director of Namati's citizenship program in Kenya, which trains locals in developing countries to be legal advocates. "You don't exist in the eyes of the state."

Goodwin is based in Kenya, where around 9 percent of the population over age 15 lacks a national ID, or about 2.7 million people. In Nairobi, Namati trains local Kenyans to become paralegals and help other Kenyans to get IDs, including Mahmoud.

"The vulnerability of not having an ID opens people up to exploitation and corruption," Goodwin said.

Within a city or between cities there are often police checkpoints where a traveler needs to have an ID. To fill out a police report, or enter a government building, you may need an ID, including to go to court. Sometimes, without an ID, people are asked to pay a bribe to the police, Goodwin said.

Even with the number of Kenyans who lack IDs, the country still fares better than many others.

Of the 1 billion people without IDs, 81 percent live in sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia. South Sudan, Chad and Armenia are among the countries with the highest share of unregistered population, according to World Bank data on people over age 15. Those countries also have a high rate of the population without a birth registration. For example, UNICEF data shows that only 35 percent of the population in South Sudan has a birth registration, and only 12 percent in Chad.

"Without a secure and trusted way to prove their identity, people struggle to open a bank account, enroll in school, access health and social services, or obtain a mobile phone," said Vyjayanti Desai, program manager for the ID4D Initiative.

The obstacles people face in getting an ID may be the result of discrimination, illiteracy, large distances to ID registration points, cost, time, and not knowing their right to an ID.

Many countries with large populations of residents without IDs also have high measures of corruption, discrimination or improper government influence in their civil justice systems, according to data from the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index. The index ranks countries based on the quality of their justice systems, and is separate from World Bank data but shows some overlap. In many of the worst-ranked countries for civil justice, nearly 20 percent of the population over the age of 15 does not have an ID.

That includes Guatemala, Cameroon, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

"Access to justice is being able to obtain a just resolution and enforce your rights," said Sarah Long, director of the Rule of Law Index. "Having legal ID helps people assert their rights when they run into issues accessing basic public services and benefits they're entitled to."

Once a person has one legal problem, that can snowball into more legal issues, according to Long, who calls that "problem clustering."

"Problems with legal identity or citizenship can bring about other legal problems, such as trouble accessing health care, education or other public services," Long said.

The ID problem appears to be worse among women.

According to the 2017 ID4D-Findex survey, in low-income countries more than 45 percent of women lack an ID, compared to 30 percent of men, a situation that disproportionately limits how women can participate in economic and political life in their country.

For example, in Afghanistan, half of the women surveyed did not have an ID compared with 6 percent of the men surveyed. In Chad, nearly 80 percent of women lacked an ID, compared with 45 percent of men.

A variety of social barriers can play into those gaps.

Child marriage is more common among women in countries with relatively few women with IDs, and in those countries women are less likely to participate in the labor force, according to the World Bank.

In Afghanistan, Benin, and Pakistan — all countries with ID gender gaps of more than 15 percentage points — a married woman can't even apply for a national ID in the same way as a married man, according to the World Bank in its Women, Business and Law report.

There is also a connection between a country's income and IDs.

According to ID4D data, 63 percent of people without IDs live in lower-middle income economies, and 28 percent live in low-income economies.

Those numbers reinforce the fact "that lack of identification is a critical concern for the global poor," Desai wrote on a World Bank blog.

Momentum could be building to tackle the ID problem, though the path forward remains hazy.

The United Nations has made the issue one of its "sustainable development goals" and set a target that by 2030 there will be legal identity for all, including birth registration. However, it hasn't specified how it plans to reach that target.

But some progress is being made. A U.N. report from 2018 shows that more children in sub-Saharan Africa under age 5 now have birth registration than in 2016. Some countries, such as Malawi, have made huge strides. Between 2017, when the World Bank collected data, and 2018, Malawi's population went from 87 percent of people without ID to about 90 percent with an ID.

Multiplying such gains will take a holistic approach, according to experts.

Goodwin, who works with populations in Bangladesh and Kenya who face exclusion and discrimination, points out that even when more people in a country gain IDs, it's important to address the underlying barriers.

She said it's important to ask, "Who is getting left out?"

--Editing by Brian Baresch.

Data from the ID4D Findex Survey was collected as part of the 2017 Gallup World Poll and includes data from 99 economies. Survey respondents were over age 15 and asked whether they personally had a specific national ID. Birth certificates, voter IDs, etc. were not included. The percentages of a population without an ID are estimates, as there is no standard, agreed-upon approach to measure the number of people without legal identity.

By The Numbers

Trump Faces Long Odds In Race To Fill The Trial Courts

By Annie Pancak and Amanda James | September 10, 2019, 8:04 PM

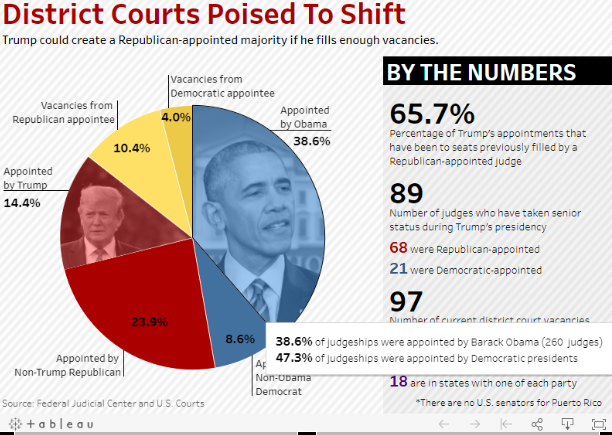

With appellate vacancies down to a handful, President Donald Trump is now turning his attention to the district courts, where he is expected to push to fill as many seats as possible before the 2020 elections.

Trump has been filling district court seats at a decent clip, but his appointment rate will likely slow during the final year of his term as the majority of the remaining vacancies lie in states with Democratic senators.

Trump had the advantage of entering office with double the number of district court vacancies that President Barack Obama had entered with and has had more nominees confirmed than his predecessor did at the same point in his first term.

But the president has been relying on a strategy that others have found tried and true: turning first to seats in politically friendly districts, before tackling vacancies in states where he’s likely to face more opposition.

The blue slip policy gives home-state senators the ability to veto a nominee, and while it was abandoned by the Republican majority earlier this year for the appellate courts, the process remains in effect for appointments to the lower courts.

With that policy in place, and the bulk of vacancies in Democrat-controlled states, Trump will have a tough time filling the 61 district court vacancies needed to get a Republican-appointed majority in the trial courts before the 2020 elections — let alone fill all the vacancies, as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., pledged last week.

"That would really depend on a second term. It's unlikely in the next 18 months, especially if he honors the blue slip," former Southern District of New York Judge Shira Scheindlin said.

Tackling the Low-Hanging Fruit

Trump entered office with 88 judicial vacancies to fill across the 91 Article III district courts. More than 2½ years later, as of Sept. 10, he has made 99 appointments, more than Obama made at this point in his presidency with a Democratic majority in the Senate, but fewer than President George W. Bush made with either party in control of the Senate at different points.

One reason Trump’s overall rate of appointment may be slightly higher than it has been at this point in some past presidencies is that almost four times as many Republican-appointed judges have taken senior status as Democratic-appointed judges during this time.

It’s typical for judges to take senior status when the party that appointed them occupies the White House, but the overall rate of judges taking senior status has been slightly higher during Trump’s presidency than it has been at this point in past presidencies.

For example, in the District of New Jersey, all four vacancies that have opened up since Trump took office were from Republican-appointed judges assuming senior status or retiring. In the Southern District of New York, two of the three judges who have taken senior status since Trump took office were appointed by a Republican president.

Scheindlin, in speculating about Trump’s prospects for filling the bench in her former court, said current Democrat-appointed judges who might be eligible for senior status are likely playing the political waiting game and holding off till they see what happens in the next election.

“It’s not always predictable that because someone is appointed by a certain president that they’ll rule a certain way,” Scheindlin said. “I’m hoping every judge when they’re appointed puts politics aside and rules according to facts regardless of what party they were in before they took the bench.”

Presidents tend to first prioritize filling vacancies in politically favorable districts, according to Harvard University researchers Justin Pottle and Jon Rogowski, who studied vacancies and nominations in federal district courts from 1961 to 2018.

These districts have connections with advocacy groups coupled with allies in the Senate who help accelerate the White House’s vetting process.

Trump’s strategy is no exception: Go after the easy targets first.

After taking office, his first two district court nominees were to Oklahoma’s western district and Idaho, two states Trump won in the 2016 election.

In states with two Republican senators, Trump has succeeded in filling multiple vacancies, including 10 judgeships in Texas’ northern and eastern districts.

In these states, the president has a better chance of pushing through more controversial candidates because he is more likely to have the backing of home-state senators, according to experts.

For example, in Oklahoma, Judge Patrick Wyrick was confirmed to the western district by a 53-47 vote. Democrats called Wyrick too extreme after he frequently opposed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency when he was Oklahoma's solicitor general.

Political Gridlock Ahead

But in districts where disagreement between home-state senators and Senate leaders can result in delays to the confirmation process, nominees tend to fall less in line ideologically with the White House’s agenda and are less controversial.

“You can’t have an extreme person on the left because the president won’t appoint, and you can’t have an extreme person on the right because the Democratic senator won’t send in the blue slip,” said Arthur Hellman, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh.

This nuance has already played out in several districts with Democratic senators.

For example, Maryellen Noreika, who was nominated to the District of Delaware by Trump, was also praised by Delaware Sens. Chris Coons and Tom Carper, who are both Democrats.

But in New York, where there has been a partisan standoff between Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., and Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., Trump renominated nine of his choices in various districts this year after their nominations from last year expired without a vote. Those nominations are still pending.

There are still several vacancies left in districts politically aligned with Trump, but many more are in states where there are two Democratic senators or one from each party.

California tops the list by number of district court vacancies with 14 judgeships waiting to be filled, while New York comes in a close second with 13 vacancies.

The administration has already shown signs of turning its attention to tackling these districts. After an initial round of nominations in February, Trump named three more judges to California’s central district in August, for a total of six. He made a second and third nomination to California’s southern district the same month. This shows a turning of the tide after ignoring the districts the first two years of his presidency, despite its high number of vacancies.

As Trump continues to pivot towards filling vacancies in these districts, he’s likely to "put packages together,” Hellman said.

This means having to negotiate with senators from those states to find “one or two [judges] that would ordinarily be unacceptable to one side or the other packaged with some that are at least tolerable for everybody.”

Such nominations are likely to take much longer than the nominations during the first half of his term because of the extensive vetting process the White House will have to conduct in addition to the negotiations with home-state senators, and the rate of appointments may slow down, as they have for most recent presidents.

That is, unless Lindsey Graham, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, chooses to abandon the blue slip policy as he did for the appellate courts, which would make it easier, technically, to appoint district court judges.

Rules Changes Smooth the Way

While Trump entered office with a high number of vacancies, he has also benefited from the 2013 abolition of the filibuster, according to Kenneth Manning, a political science professor at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth.

Trump’s path was further smoothed by a Senate vote in April shortening the number of hours of debate allowed on nominees from 30 hours to two, according to political science professor Sheldon Goldman at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Trump has had 99 district court judges, or 70% of his nominees, confirmed by Sept. 10. Two of those appointees — Peter J. Phipps and A. Marvin Quattlebaum Jr. — were subsequently elevated to circuit courts, bringing the number of active district court appointees to 97. Obama, on the other hand, had 74, or 62%, of his district court nominees confirmed at the same point in his presidency.

"The rules are much more conducive now to an administration getting their judges approved as long as their party controls the Senate,” Manning said.

And yet, even though Trump has faced fewer obstacles than Obama did, during the first Congress of Trump’s term there was a “surprisingly high” amount of opposition to nominees many considered controversial, Goldman noted.

He expects a big push to get nominees to the district courts confirmed by this fall, ahead of the 2020 elections.

“Trump’s impact would be greater if all the vacancies were filled, and I think the impact for the district courts will be felt when this Congress is finished,” Goldman said.

District courts have significant reach and power in interpreting the law. Appellate courts, which hear thousands of cases compared to the 75 to 80 the Supreme Court hears each year, have affirmed lower court decisions more than 60% of the time in the last three years, according to the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

"The reality is when cases are decided by the U.S. district court, in most instances, those decisions stand," Manning said.

Annie Pancak and Amanda James are data reporters for Law360. Graphics by Chris Yates. Editing by Pamela Wilkinson, Jocelyn Allison and John Campbell.

Trump Faces Long Odds In Race To Fill The Trial Courts

By Annie Pancak and Amanda James | September 10, 2019, 8:04 PM

With appellate vacancies down to a handful, President Donald Trump is now turning his attention to the district courts, where he is expected to push to fill as many seats as possible before the 2020 elections.

Trump has been filling district court seats at a decent clip, but his appointment rate will likely slow during the final year of his term as the majority of the remaining vacancies lie in states with Democratic senators.

Trump had the advantage of entering office with double the number of district court vacancies that President Barack Obama had entered with and has had more nominees confirmed than his predecessor did at the same point in his first term.

But the president has been relying on a strategy that others have found tried and true: turning first to seats in politically friendly districts, before tackling vacancies in states where he’s likely to face more opposition.

The blue slip policy gives home-state senators the ability to veto a nominee, and while it was abandoned by the Republican majority earlier this year for the appellate courts, the process remains in effect for appointments to the lower courts.

With that policy in place, and the bulk of vacancies in Democrat-controlled states, Trump will have a tough time filling the 61 district court vacancies needed to get a Republican-appointed majority in the trial courts before the 2020 elections — let alone fill all the vacancies, as Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., pledged last week.

"That would really depend on a second term. It's unlikely in the next 18 months, especially if he honors the blue slip," former Southern District of New York Judge Shira Scheindlin said.

Tackling the Low-Hanging Fruit

Trump entered office with 88 judicial vacancies to fill across the 91 Article III district courts. More than 2½ years later, as of Sept. 10, he has made 99 appointments, more than Obama made at this point in his presidency with a Democratic majority in the Senate, but fewer than President George W. Bush made with either party in control of the Senate at different points.

One reason Trump’s overall rate of appointment may be slightly higher than it has been at this point in some past presidencies is that almost four times as many Republican-appointed judges have taken senior status as Democratic-appointed judges during this time.

It’s typical for judges to take senior status when the party that appointed them occupies the White House, but the overall rate of judges taking senior status has been slightly higher during Trump’s presidency than it has been at this point in past presidencies.

For example, in the District of New Jersey, all four vacancies that have opened up since Trump took office were from Republican-appointed judges assuming senior status or retiring. In the Southern District of New York, two of the three judges who have taken senior status since Trump took office were appointed by a Republican president.

Scheindlin, in speculating about Trump’s prospects for filling the bench in her former court, said current Democrat-appointed judges who might be eligible for senior status are likely playing the political waiting game and holding off till they see what happens in the next election.

“It’s not always predictable that because someone is appointed by a certain president that they’ll rule a certain way,” Scheindlin said. “I’m hoping every judge when they’re appointed puts politics aside and rules according to facts regardless of what party they were in before they took the bench.”

Presidents tend to first prioritize filling vacancies in politically favorable districts, according to Harvard University researchers Justin Pottle and Jon Rogowski, who studied vacancies and nominations in federal district courts from 1961 to 2018.

These districts have connections with advocacy groups coupled with allies in the Senate who help accelerate the White House’s vetting process.

Trump’s strategy is no exception: Go after the easy targets first.

After taking office, his first two district court nominees were to Oklahoma’s western district and Idaho, two states Trump won in the 2016 election.

In states with two Republican senators, Trump has succeeded in filling multiple vacancies, including 10 judgeships in Texas’ northern and eastern districts.

In these states, the president has a better chance of pushing through more controversial candidates because he is more likely to have the backing of home-state senators, according to experts.

For example, in Oklahoma, Judge Patrick Wyrick was confirmed to the western district by a 53-47 vote. Democrats called Wyrick too extreme after he frequently opposed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency when he was Oklahoma's solicitor general.

Political Gridlock Ahead

But in districts where disagreement between home-state senators and Senate leaders can result in delays to the confirmation process, nominees tend to fall less in line ideologically with the White House’s agenda and are less controversial.

“You can’t have an extreme person on the left because the president won’t appoint, and you can’t have an extreme person on the right because the Democratic senator won’t send in the blue slip,” said Arthur Hellman, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh.

This nuance has already played out in several districts with Democratic senators.

For example, Maryellen Noreika, who was nominated to the District of Delaware by Trump, was also praised by Delaware Sens. Chris Coons and Tom Carper, who are both Democrats.

But in New York, where there has been a partisan standoff between Sen. Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., and Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., Trump renominated nine of his choices in various districts this year after their nominations from last year expired without a vote. Those nominations are still pending.

There are still several vacancies left in districts politically aligned with Trump, but many more are in states where there are two Democratic senators or one from each party.

California tops the list by number of district court vacancies with 14 judgeships waiting to be filled, while New York comes in a close second with 13 vacancies.

The administration has already shown signs of turning its attention to tackling these districts. After an initial round of nominations in February, Trump named three more judges to California’s central district in August, for a total of six. He made a second and third nomination to California’s southern district the same month. This shows a turning of the tide after ignoring the districts the first two years of his presidency, despite its high number of vacancies.

As Trump continues to pivot towards filling vacancies in these districts, he’s likely to "put packages together,” Hellman said.

This means having to negotiate with senators from those states to find “one or two [judges] that would ordinarily be unacceptable to one side or the other packaged with some that are at least tolerable for everybody.”

Such nominations are likely to take much longer than the nominations during the first half of his term because of the extensive vetting process the White House will have to conduct in addition to the negotiations with home-state senators, and the rate of appointments may slow down, as they have for most recent presidents.

That is, unless Lindsey Graham, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, chooses to abandon the blue slip policy as he did for the appellate courts, which would make it easier, technically, to appoint district court judges.

Rules Changes Smooth the Way

While Trump entered office with a high number of vacancies, he has also benefited from the 2013 abolition of the filibuster, according to Kenneth Manning, a political science professor at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth.

Trump’s path was further smoothed by a Senate vote in April shortening the number of hours of debate allowed on nominees from 30 hours to two, according to political science professor Sheldon Goldman at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Trump has had 99 district court judges, or 70% of his nominees, confirmed by Sept. 10. Two of those appointees — Peter J. Phipps and A. Marvin Quattlebaum Jr. — were subsequently elevated to circuit courts, bringing the number of active district court appointees to 97. Obama, on the other hand, had 74, or 62%, of his district court nominees confirmed at the same point in his presidency.

"The rules are much more conducive now to an administration getting their judges approved as long as their party controls the Senate,” Manning said.

And yet, even though Trump has faced fewer obstacles than Obama did, during the first Congress of Trump’s term there was a “surprisingly high” amount of opposition to nominees many considered controversial, Goldman noted.

He expects a big push to get nominees to the district courts confirmed by this fall, ahead of the 2020 elections.

“Trump’s impact would be greater if all the vacancies were filled, and I think the impact for the district courts will be felt when this Congress is finished,” Goldman said.

District courts have significant reach and power in interpreting the law. Appellate courts, which hear thousands of cases compared to the 75 to 80 the Supreme Court hears each year, have affirmed lower court decisions more than 60% of the time in the last three years, according to the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts.

"The reality is when cases are decided by the U.S. district court, in most instances, those decisions stand," Manning said.

Annie Pancak and Amanda James are data reporters for Law360. Graphics by Chris Yates. Editing by Pamela Wilkinson, Jocelyn Allison and John Campbell.

By The Numbers

Gender Disparity At The High Court: How Top Law Firms Measure Up

By Amanda James and Annie Pancak | October 15, 2018

In the first sitting of the new U.S. Supreme Court term this month, six women stepped up to the podium to argue cases on issues ranging from the scope of the Federal Arbitration Act to the rights of landowners in federal court.

By contrast, 16 arguments were made by men. While still far short of gender parity, it was a more promising start for women who seek to argue cases before the nation’s highest court.

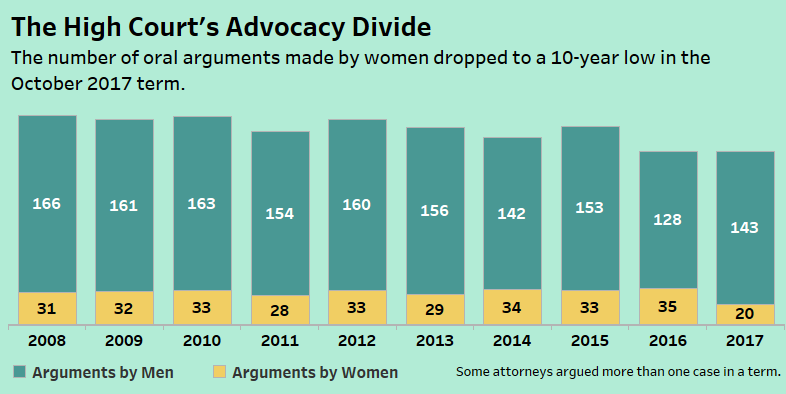

Last October, three women stepped up to the podium during that first two-week period, and the term ended with the rate of arguments made by women hitting a 10-term low. In the last 10 completed terms, the percentage of arguments handled by women at the Supreme Court was 17 percent. But in the 2017 term, that number hit 12 percent.

Law360 did an in-depth data study to pinpoint where the disparity starts. We looked at all of the attorneys who have argued in the Supreme Court over the last 10 completed terms — 616 men, compared to 125 women — and found the firms with the highest, and lowest, rate of putting a woman behind the podium at 1 First St.

Of the 10 firms that have argued most frequently before the high court in the last decade, four have put no women up for oral argument during that time: Sidley Austin LLP, Mayer Brown LLP, Kellogg Hansen Todd Figel & Frederick PLLC and Jones Day. All either did not respond to multiple requests for comment or declined to address the matter.

Only seven law firms have had at least four oral arguments before the high court by female lawyers over the past 10 terms — and many of those arguments have been handled by the same woman. The number of individual women who argued last term also dropped, from 21 in the 2016 term to 16 in 2017.

With so few women involved in directing rulings that affect the nation, the court risks losing a substantial viewpoint, advocates and scholars say.

“If that female voice is lost at the Supreme Court, that impacts the case law that affects everyone, and only about half of the population is having its voice heard at the court,” said Texas A&M political science professor Shane Gleason.

How law firms determine who argues cases depends on a range of factors, not the least of which is the preference of the client. Sometimes the argument will go to whoever worked on the case in the lower court, and other times it will be argued by whoever brought in the client.

One key factor is star power. Of the attorneys who ranked as one of the Top 10 most frequent arguers of the last decade, five were former solicitors general or acting solicitors general, all of whom are men.

“The former SGs and former acting SGs get a huge number of arguments, and they’re all men right now … so that sucks up a lot of the oxygen,” said Sarah Harrington, who worked at the SG’s office as an assistant for eight years before moving to Goldstein & Russell PC in 2017.

This means that arguments can often end up a one-man show. For example, Seth Waxman, who was the solicitor general from 1997-2001, has argued more than half of WilmerHale’s cases in the last 10 years — 28 of 49. And Paul Clement, who was the solicitor general from 2005-08, argued six of Kirkland’s eight cases at the high court last term.

Of the firms that argued before the Supreme Court the most in the past decade, Jenner & Block tops the list of most likely to put a female advocate before the high court. With four cases argued by women and 19 argued by men in the past 10 terms, the firm’s rate of women-argued cases stands at 17.4 percent.

At the firms that have put no women before the court in the past 10 terms, some rely on the same man for the majority of oral arguments, whereas others divide them evenly among a wide pool of male advocates.

At Sidley, partner Carter Phillips argued 26 out of the firm's 39 arguments over the past 10 completed terms. A former firm chairman, Philips holds the record for the most Supreme Court arguments by an attorney in private practice, beyond the 10 terms of this study.

At Mayer Brown, most of the cases were argued by Charles Rothfeld and Andrew Pincus, who are leaders of the Yale Law School Supreme Court Clinic. The firm's appellate practice is co-chaired by three attorneys: Pincus, Evan Tager and Lauren R. Goldman. Tager also argues cases in the Supreme Court, and Goldman is working on cases in the Ninth Circuit.

At D.C.-based litigation boutique Kellogg Hansen, most of the firm’s 35 arguments at the Supreme Court in the last 10 terms were handled by David Frederick, a former clerk for Justice Byron R. White.

The 32 arguments from Jones Day over the last 10 terms were distributed among 16 different men, with Michael Carvin, who argued on behalf of petitioners in King v. Burwell, and Shay Dvoretzky, a former clerk for Justice Antonin Scalia, handling the most.

In the past 10 terms, seven firms have had at least four oral arguments by women at the high court. Quinn Emanuel has had the most cases argued by women, followed by Arnold & Porter and WilmerHale, who are tied for the second most.

Quinn Emanuel, Arnold & Porter and Akin Gump more often have women argue before the high court than men, though all of those arguments have been handled by one or two women. At Quinn Emanuel, practice chair Kathleen Sullivan argued seven cases, and Sheila L. Birnbaum, who is now a partner at Dechert LLP, argued one.

At Arnold & Porter, Lisa Blatt, who has a near-perfect high court win record, has been the sole female arguer, with seven arguments in the past decade. Most recently, Blatt notched a win for a group of hospitals in a three-case argument over ERISA’s religious exemption provision.

WilmerHale’s cases have been argued by Catherine Carroll and Danielle Spinelli. Carroll, who is a former clerk for Justice David H. Souter, has argued three cases in the past 10 terms, most recently arguing on behalf of Helmerich & Payne in foreign expropriation case Venezuela v. Helmerich & Payne Int'l .

Spinelli, a former clerk for Justice Stephen Breyer and vice chair of WilmerHale’s appellate and Supreme Court practice group, has argued four cases in the past decade. She most recently argued on behalf of creditors in bankruptcy case Czyzewski v. Jevic Holding Corp.

All six of the female-argued cases at Akin Gump were carried out by Patricia Millett, who is now a judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.

At Morgan Lewis, Allyson Ho argued four of the firm’s six cases over the last decade, including a win in April 2017 in McLane v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission , when the justices ruled that federal appeals courts should use a deferential standard to review trial court decisions on enforcement of EEOC subpoenas. Ho recently moved her practice to Gibson Dunn.

At Jenner, 17 percent of its Supreme Court appearances included a woman. Catherine Steege, Elaine Goldenberg — who's now at Munger Tolles & Olsen LLP following a stint in the solicitor general's office — Jessica Amunson and Lindsay Harrison each argued one case. Last term, Amunson successfully argued in Class v. U.S. , when the justices ruled that criminal defendants can challenge the constitutionality of laws they already pled guilty to breaking if they didn't explicitly waive the right to do so.

And at Kirkland, all four cases were argued by Erin Murphy, who argued last term for the Wisconsin State Senate as amicus in the gerrymandering case Gill v. Whitford.

A significant proportion of female advocates before the court in the past decade were women from the solicitor general’s office, so the dropping numbers of women from that office arguing cases could signal a lessening of opportunities for women.

Out of 58 cases argued by the solicitor general’s office in the 2008 term, 24 percent — 14 cases — were argued by women. A decade later, in 2017, about 19 percent — or nine cases — were argued by women.

Prior to this drop, women argued 19 cases on behalf of the solicitor general’s office in 2016.

Six women left the office in the last year. Several of the women who left called the surge in departures “coincidental.”

The number of female assistants to the solicitor general leaving had an effect on the presence of women in the courtroom. In 2016, seven women argued cases on behalf of the federal government, and in 2017 that number dropped to five.

Harrington, one of the women who left the SG’s office for private practice last year, said the gender balance of high court advocates will begin to shift once women start occupying the roles of solicitor general and deputy solicitor general, posts currently held by men.

“It’s all because each level is dependent on the level before,” she said. “We need some change at the bottom. I think the gender disparity among private practice lawyers in the Supreme Court is going to be the last thing to change.”

Some say the change is only a matter of time. Men who are arguing the most cases are later in their careers than women arguing the most cases. On average, the Top 10 men with the most arguments have been out of law school 33 years; for women, it’s about 20 years.

“I think there will be generational change and we’ll see it in the next few years,” said Sullivan, the Quinn Emanuel practice chair.

Methodology: Law360 counted all advocates who appeared in the transcript of each oral argument before the U.S. Supreme Court from the 2008 term through the 2017 term. The law firm or organization the attorney is affiliated with was verified in documents filed with the Supreme Court if it is unclear from the transcript. Some cases have more than one oral argument. This data counts each of those arguments separately.

The data for law firms represents a combination of the arguments made by a law firm in its current form, as well as any identifiable predecessor law firms. For example, Hogan Lovells’ numbers include arguments made by Hogan & Hartson. Goldstein & Russell PC’s numbers include arguments made by Goldstein Howe & Russell and Howe & Russell. Kirkland & Ellis LLP’s arguments include arguments made by Bancroft. Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer LLP’s arguments include those made by Arnold & Porter and Kaye Scholer. Kellogg Hansen Todd Figel & Frederick PLLC’s numbers include arguments made by Kellogg Huber Hansen Todd Evans & Figel.

Our analysis of law firms does not include solo practitioners.

Amanda James and Annie Pancak are data reporters for Law360 who also contributed to the first installment in this special report. Additional reporting and data analysis by senior data reporter Jacqueline Bell. Graphics by Jonathan Hayter. Editing by Jocelyn Allison and Rebecca Flanagan.

Gender Disparity At The High Court: How Top Law Firms Measure Up

By Amanda James and Annie Pancak | October 15, 2018

In the first sitting of the new U.S. Supreme Court term this month, six women stepped up to the podium to argue cases on issues ranging from the scope of the Federal Arbitration Act to the rights of landowners in federal court.

By contrast, 16 arguments were made by men. While still far short of gender parity, it was a more promising start for women who seek to argue cases before the nation’s highest court.

Last October, three women stepped up to the podium during that first two-week period, and the term ended with the rate of arguments made by women hitting a 10-term low. In the last 10 completed terms, the percentage of arguments handled by women at the Supreme Court was 17 percent. But in the 2017 term, that number hit 12 percent.

Law360 did an in-depth data study to pinpoint where the disparity starts. We looked at all of the attorneys who have argued in the Supreme Court over the last 10 completed terms — 616 men, compared to 125 women — and found the firms with the highest, and lowest, rate of putting a woman behind the podium at 1 First St.

Of the 10 firms that have argued most frequently before the high court in the last decade, four have put no women up for oral argument during that time: Sidley Austin LLP, Mayer Brown LLP, Kellogg Hansen Todd Figel & Frederick PLLC and Jones Day. All either did not respond to multiple requests for comment or declined to address the matter.

Only seven law firms have had at least four oral arguments before the high court by female lawyers over the past 10 terms — and many of those arguments have been handled by the same woman. The number of individual women who argued last term also dropped, from 21 in the 2016 term to 16 in 2017.

With so few women involved in directing rulings that affect the nation, the court risks losing a substantial viewpoint, advocates and scholars say.

“If that female voice is lost at the Supreme Court, that impacts the case law that affects everyone, and only about half of the population is having its voice heard at the court,” said Texas A&M political science professor Shane Gleason.

How law firms determine who argues cases depends on a range of factors, not the least of which is the preference of the client. Sometimes the argument will go to whoever worked on the case in the lower court, and other times it will be argued by whoever brought in the client.

One key factor is star power. Of the attorneys who ranked as one of the Top 10 most frequent arguers of the last decade, five were former solicitors general or acting solicitors general, all of whom are men.

“The former SGs and former acting SGs get a huge number of arguments, and they’re all men right now … so that sucks up a lot of the oxygen,” said Sarah Harrington, who worked at the SG’s office as an assistant for eight years before moving to Goldstein & Russell PC in 2017.

This means that arguments can often end up a one-man show. For example, Seth Waxman, who was the solicitor general from 1997-2001, has argued more than half of WilmerHale’s cases in the last 10 years — 28 of 49. And Paul Clement, who was the solicitor general from 2005-08, argued six of Kirkland’s eight cases at the high court last term.

Of the firms that argued before the Supreme Court the most in the past decade, Jenner & Block tops the list of most likely to put a female advocate before the high court. With four cases argued by women and 19 argued by men in the past 10 terms, the firm’s rate of women-argued cases stands at 17.4 percent.

At the firms that have put no women before the court in the past 10 terms, some rely on the same man for the majority of oral arguments, whereas others divide them evenly among a wide pool of male advocates.

At Sidley, partner Carter Phillips argued 26 out of the firm's 39 arguments over the past 10 completed terms. A former firm chairman, Philips holds the record for the most Supreme Court arguments by an attorney in private practice, beyond the 10 terms of this study.

At Mayer Brown, most of the cases were argued by Charles Rothfeld and Andrew Pincus, who are leaders of the Yale Law School Supreme Court Clinic. The firm's appellate practice is co-chaired by three attorneys: Pincus, Evan Tager and Lauren R. Goldman. Tager also argues cases in the Supreme Court, and Goldman is working on cases in the Ninth Circuit.

At D.C.-based litigation boutique Kellogg Hansen, most of the firm’s 35 arguments at the Supreme Court in the last 10 terms were handled by David Frederick, a former clerk for Justice Byron R. White.

The 32 arguments from Jones Day over the last 10 terms were distributed among 16 different men, with Michael Carvin, who argued on behalf of petitioners in King v. Burwell, and Shay Dvoretzky, a former clerk for Justice Antonin Scalia, handling the most.

In the past 10 terms, seven firms have had at least four oral arguments by women at the high court. Quinn Emanuel has had the most cases argued by women, followed by Arnold & Porter and WilmerHale, who are tied for the second most.

Quinn Emanuel, Arnold & Porter and Akin Gump more often have women argue before the high court than men, though all of those arguments have been handled by one or two women. At Quinn Emanuel, practice chair Kathleen Sullivan argued seven cases, and Sheila L. Birnbaum, who is now a partner at Dechert LLP, argued one.

At Arnold & Porter, Lisa Blatt, who has a near-perfect high court win record, has been the sole female arguer, with seven arguments in the past decade. Most recently, Blatt notched a win for a group of hospitals in a three-case argument over ERISA’s religious exemption provision.

WilmerHale’s cases have been argued by Catherine Carroll and Danielle Spinelli. Carroll, who is a former clerk for Justice David H. Souter, has argued three cases in the past 10 terms, most recently arguing on behalf of Helmerich & Payne in foreign expropriation case Venezuela v. Helmerich & Payne Int'l .

Spinelli, a former clerk for Justice Stephen Breyer and vice chair of WilmerHale’s appellate and Supreme Court practice group, has argued four cases in the past decade. She most recently argued on behalf of creditors in bankruptcy case Czyzewski v. Jevic Holding Corp.

All six of the female-argued cases at Akin Gump were carried out by Patricia Millett, who is now a judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.

At Morgan Lewis, Allyson Ho argued four of the firm’s six cases over the last decade, including a win in April 2017 in McLane v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission , when the justices ruled that federal appeals courts should use a deferential standard to review trial court decisions on enforcement of EEOC subpoenas. Ho recently moved her practice to Gibson Dunn.

At Jenner, 17 percent of its Supreme Court appearances included a woman. Catherine Steege, Elaine Goldenberg — who's now at Munger Tolles & Olsen LLP following a stint in the solicitor general's office — Jessica Amunson and Lindsay Harrison each argued one case. Last term, Amunson successfully argued in Class v. U.S. , when the justices ruled that criminal defendants can challenge the constitutionality of laws they already pled guilty to breaking if they didn't explicitly waive the right to do so.

And at Kirkland, all four cases were argued by Erin Murphy, who argued last term for the Wisconsin State Senate as amicus in the gerrymandering case Gill v. Whitford.

A significant proportion of female advocates before the court in the past decade were women from the solicitor general’s office, so the dropping numbers of women from that office arguing cases could signal a lessening of opportunities for women.

Out of 58 cases argued by the solicitor general’s office in the 2008 term, 24 percent — 14 cases — were argued by women. A decade later, in 2017, about 19 percent — or nine cases — were argued by women.

Prior to this drop, women argued 19 cases on behalf of the solicitor general’s office in 2016.

Six women left the office in the last year. Several of the women who left called the surge in departures “coincidental.”

The number of female assistants to the solicitor general leaving had an effect on the presence of women in the courtroom. In 2016, seven women argued cases on behalf of the federal government, and in 2017 that number dropped to five.

Harrington, one of the women who left the SG’s office for private practice last year, said the gender balance of high court advocates will begin to shift once women start occupying the roles of solicitor general and deputy solicitor general, posts currently held by men.

“It’s all because each level is dependent on the level before,” she said. “We need some change at the bottom. I think the gender disparity among private practice lawyers in the Supreme Court is going to be the last thing to change.”

Some say the change is only a matter of time. Men who are arguing the most cases are later in their careers than women arguing the most cases. On average, the Top 10 men with the most arguments have been out of law school 33 years; for women, it’s about 20 years.

“I think there will be generational change and we’ll see it in the next few years,” said Sullivan, the Quinn Emanuel practice chair.

Methodology: Law360 counted all advocates who appeared in the transcript of each oral argument before the U.S. Supreme Court from the 2008 term through the 2017 term. The law firm or organization the attorney is affiliated with was verified in documents filed with the Supreme Court if it is unclear from the transcript. Some cases have more than one oral argument. This data counts each of those arguments separately.

The data for law firms represents a combination of the arguments made by a law firm in its current form, as well as any identifiable predecessor law firms. For example, Hogan Lovells’ numbers include arguments made by Hogan & Hartson. Goldstein & Russell PC’s numbers include arguments made by Goldstein Howe & Russell and Howe & Russell. Kirkland & Ellis LLP’s arguments include arguments made by Bancroft. Arnold & Porter Kaye Scholer LLP’s arguments include those made by Arnold & Porter and Kaye Scholer. Kellogg Hansen Todd Figel & Frederick PLLC’s numbers include arguments made by Kellogg Huber Hansen Todd Evans & Figel.

Our analysis of law firms does not include solo practitioners.

Amanda James and Annie Pancak are data reporters for Law360 who also contributed to the first installment in this special report. Additional reporting and data analysis by senior data reporter Jacqueline Bell. Graphics by Jonathan Hayter. Editing by Jocelyn Allison and Rebecca Flanagan.